Back to Homepage

Press about Jon Waterman and ‘Live Music Making History Live’

From the Martha’s Vineyard Times, Dec. 31, 2019:

https://www.mvtimes.com/2019/12/31/american-musical-journey/

An American musical journey

Jon Waterman presents history through popular music.

By Abby Remer

December 31, 2019

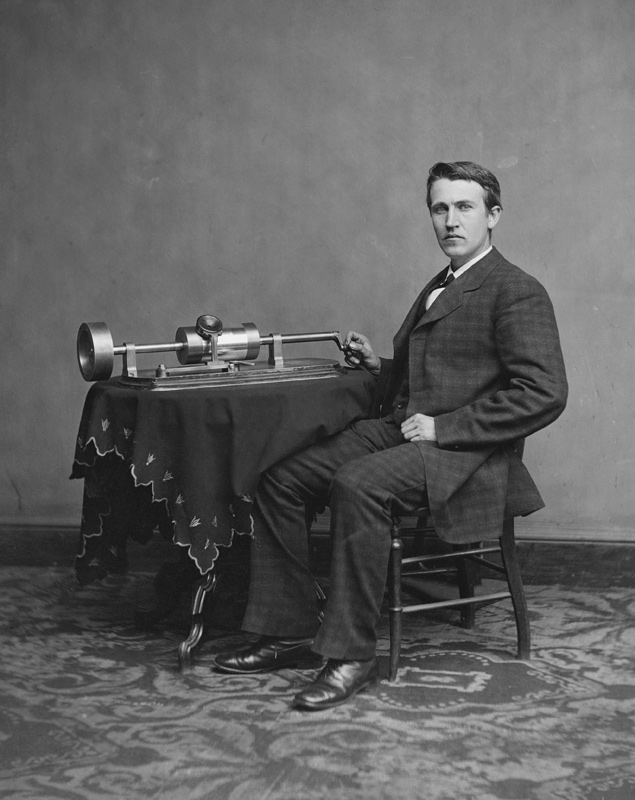

In 1877, Thomas Edison created a machine with two needles: one for recording and one for playback. — Wikimedia Commons

One thing you can say about American popular music: it’s a complex issue. Jon Waterman’s engrossing singing and guitar playing about its roots was the perfect way to enjoy the lull between the holiday celebrations and New Year’s revelry. The Oak Bluffs library hosted his presentation last Saturday.

For Waterman, American popular music is about our collective experiences and is an important part of who we are now. The afternoon was a rich, engrossing exploration and celebration of the topic through songs about music, songs about musicians, or songs that have a backstory that help to illustrate the story of popular music. He wrote all but two of them, and each made a point about the music’s origins.

Let’s start with a definition. By popular music, Waterman means: “The entirety of the music of the people that’s not considered ‘classical’ or ‘high culture’ and is intended for all or any of the people. So, I don’t think of church songs or military marches or college fight songs as popular music. Of course, there’s a lot of crossover.”

Waterman’s first song, “Press It in Wax” tells the tale of an early momentous shift that occurred with Edison’s invention of the phonograph in 1877 — and the initial recordings, which were pressed in wax cylinders. Waterman recounted how before this time music happened in a social milieu, with musicians making their living by performing. But now you could listen to music in the privacy of your own home on the phonograph or the radio. Suddenly, musicians had to get their music recorded in order to survive. The song speaks of five early talent scouts and record producers who did a lot to shape popular music in this country — Ralph Peer, Sam Phillips, John Hammond, and John and Alan Lomax.

An enigmatic theme was the question of where the Blues came from, which Waterman talked about before playing “Butler May.” Waterman shared that traditionally, it’s thought that the Blues evolved out of the field hollers, spirituals, and African folk songs of the Mississippi Delta region. An alternate theory, although not necessarily mutually exclusive, says that it evolved out of black vaudeville in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Waterman told us that Butler May was a popular performer in that circuit. His signature number was about the Titanic in which he’d stand at the piano and sway back and forth to show the ship rocking in the water. He’d slowly sink, all the while belting out this song about how he was on the Titanic yet able to swim to safety because he had the Elgin movement in his hips and “a twenty-year guarantee.” As it happens, Elgin was a watch brand and the movement of its mechanical elements came with … yep, a twenty-year guarantee. That “Elgin Movements” metaphor turns up repeatedly in the Blues. Butler May was known to be pretty vulgar and black press criticized him for being too “blue,” a vaudeville term for being vulgar on stage and may have contributed to the belief that Butler May was the original Blues man.

Waterman didn’t shy away from the difficult issue of minstrelsy in “Thomas Rice and His Traveling Review.” He began, “There are two contradictory themes you hear in the story of popular music. One is the blending of influences from the different sources of the American melting pot, and the other is the artificial and arbitrary setting aside and keeping apart of some of those influences, most notably that of black Americans. The worst of which was the emergence of minstrelsy, which became a horrible form of political propaganda in the aftermath of the Civil War.”

Waterman continued, “Minstrelsy was a vehicle through which a representation of black music was introduced to a large number of non-black Americans who had had little or no contact with them. Even as the minstrel shows became increasingly insulting and derogatory towards African Americans and other minorities, the performers in those shows, ironically, would be competing with one another for who could do the most authentic representation. So, what they were insulting and degrading they were simultaneously idealizing, which is a kind of weird juxtaposition. But the qualities in the music that they were idealizing they attributed to the irrelevant characteristic of skin color rather than to the hard work and passion of individual black artists and the openness of black culture generally. That’s basically what prejudice is, taking away credit from individuals and giving that credit to a whole population based on irrelevant criteria like skin color or ethnic origin. Sadly, that’s still here.”

For Waterman, “Popular songs tell our stories, mark events in our lives. Not just big historical events, say of World War II, but everyday experiences. And by sharing them individuals come together and start to identify as a people, as a culture, whether it’s from celebrating the heroes of the stories or the stories the heroes told. Or whether it’s from atoning for past injustices. The voices of musicians play an important part in shaping our identity as a people and in a country as divided as ours, we need that sense of commonality — that there is, in fact, an American culture and it’s in the stories and experiences that we share.”

https://www.hometownweekly.net/wellesley/jon-waterman-teaches-pop-music-history/

Jon Waterman teaches pop music history

By James Kinneen

Hometown Weekly ReporterAt most summer concerts, the most musical knowledge you’re going to get typically comes in the form of a fun fact or two about who originally performed the song.

That’s not the performers’ fault – few have the abundance of musical knowledge that Jon Waterman has.

With a Masters in Pop Music History from Prescott College, Waterman was able to present an educational concert on the roots of American popular music to cap off the Wellesley Library’s summer concert series on Wednesday, August 14.

Waterman began by noting how the invention of the phonograph made music “much less of a social experience, which was something musicians needed to adapt to.” With this happening, Ralph Peer of Victor Records heads to the South in 1927 to record the music of the southern Appalachians, believing “people in rural areas would like to hear music from people like themselves, that reflected their own lives.”

Named after the earliest ways music was recorded, Waterman’s song, “Press it in Wax,” tells this story of Peer’s sojourn to the South, which would ultimately conclude with his discovering the Carter family and Jimmie Rodgers.

Other than Peer, the song mentions Sam Phillips, as well as John and Alan Lomax. In 1934, the Lomaxes went to a prison in Sugarland, Texas, and recorded Ironhead Baker performing “St. James Infirmary Blues,” his own unique addition to the “Rake” cycle. The “Rake” cycle is a group of songs all about a dying man singing about what he’d like at his funeral, the most famous of which is “Streets of Laredo.”

While the other songs in the “Rake” cycle are in major keys, “St. James Infirmary Blues” is in a minor key. Why? While there is no conclusive answer, Waterman raised the hypothesis that it’s likely one of many black cowboys could have played “Streets of Laredo” in a minor key as it was passed back and forth between cultures.

Waterman performed “St James Infirmary Blues,” then sang “Dockery Farm,” a song about the famed plantation where so many musicians got their start, including Robert Johnson. Waterman noted that the most likely answer as to where the sound originated is that a mysterious figure named Henry Sloan taught the men that worked on the farm how to play what would become Mississippi Delta blues – though a far more fantastical version of events has the devil teaching them in exchange for their souls.

Why it’s called the blues is another mystery that has a few possible answers, but one makes more sense than others. After discussing minstrelsy and singing “Thomas Rice and his Traveling Review,” Waterman explained how one of the biggest stars of the black vaudeville scene was a young prodigy named Butler May. May was both a singer and comedian, but was criticized for being far too vulgar. Likely because of “Blue Laws,” a synonym for vulgar was blue, thus the possible origin of the “blues.”

Known for his song about his time on The Titanic (much of the song’s humor originated in the fact that blacks weren’t allowed on The Titanic), Waterman paid homage to the young man that met his unfortunate end at age 23 by performing “Butler May.”

Waterman talked about how “The Ship That Never Returned” became “The Wreck of Old 97,” which became “Charlie on the MTA.” Waterman performed “The Wreck of Old 97” after noting how the success of the song led to an “event song” craze, during which time there were all sorts of songs about fires and other disasters.

There were far more songs and stories – from how Jimmy Rodgers recorded with a Hawaiian steel guitar player (and in turn introduced the steel guitar to country music), which Waterman noted before playing “Riding With Jimmy Rodgers,” to “Hughie Cannon’s Blues,” his biography of the famed ragtime pianist.

Waterman unfortunately did not have time to cover when and where pop music eventually went so wrong, which is a shame.

The American music scene would be far better off if our most popular performers had Waterman’s talent and reverence for American music history.

Wellesley

August 22, 2019

Hometown Weekly Staff